October 24, 2024

A crucial molecule for brain health acts as a garbage collector of other fat molecules (lipids), despite also being a lipid itself.

So for more than half a century, researchers have puzzled over how these lipid molecules, called BMP, aren't disposed of with the rest of the fats they harvest.

Cell biologist Shubham Singh from the Sloan Kettering Institute in New York and colleagues have now uncovered the secret to BMP's degradation-eluding skills lies in the way a pair of molecules form it into a resistant structure.

Their findings also help to explain how abnormal levels of BMP are linked to a higher risk of dementia, including Alzheimer's.

BMP is particularly low in the brains of patients with frontotemporal dementia, allowing sugary lipids called gangliosides to accumulate.

At high levels, these molecules are toxic and produce a condition called gangliosidosis that destroys neurons in the brain and spinal cord. Treating cells with gangliosidosis in the lab with BMP leads to their recovery.

With over 10 million cases of dementia diagnosed around the world each year, more and more people experience debilitating symptoms of confusion, communication difficulties, and memory loss, either personally or in loved ones.

The more we can understand the biological pathways responsible for cognitive decline, the closer we can get to better managing these cureless conditions.

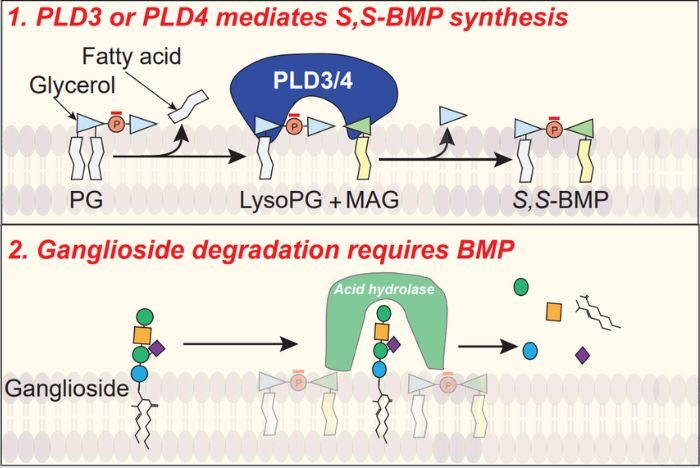

Much like our hands, molecules can have right (R) or left (S) handed configurations. BMP happens to be an oddly left-handed molecule among right-handed fats.

"Everything in lipid biochemistry starts from one molecule called glycerol 3-phosphate, and it is R," explains Singh. "So, at what step do you convert R to S, or right hand to left hand, to make BMP?"

Laboratory tests on mice and human cells revealed a pair of enzymes in cellular storage compartments called lysosomes where BMP is produced. These two proteins – called PLD3 and PLD4 – give the lipid its unique handedness.

Cornell University cell biologist Jeremy Baskin, who was not involved in the study, explains another molecule had been thought to make BMP, but it was the wrong handedness.

"We were… surprised because other people had reported that another enzyme could make BMP," says Baskin.

Crucially, changes to either of these enzymes can increase or decrease levels of BMP in the cells. A mutated form of PLD3 previously associated with Alzheimer's disease more than halved the amount of BMP produced, Singh and colleagues discovered, suggesting dysregulation of brain lipids may be playing a role in the condition.

Dementia is a complex condition involving a wide range of biological pathways, of which so few are understood. But the more researchers learn about the brain's typical functions, the closer we get to understanding the stubbornly incomprehensible diseases associated with them too.

This research was published in Cell.