October 29, 2024

Something ancient awakens in our DNA during pregnancy and moments of blood loss to drive an increased demand for red cells in the body, researchers have found.

A new study by researchers in the US and Germany has uncovered long-dormant virus fragments triggering an immune response that ramps up red blood production when it's needed most.

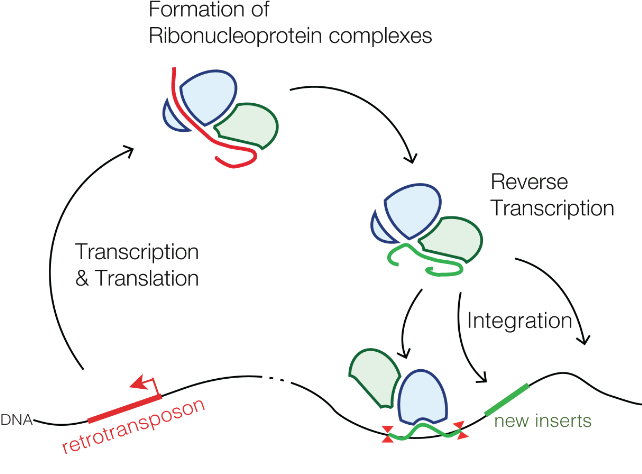

The surprising discovery was made through an analysis of hematopoietic (blood-forming) stem cells in mice, in which fragments of genetic code known as retrotransposons became activated during pregnancy.

The hematopoietic stem cells appear to unlock a viral process that cells have long forgotten. But it's not without risk; when awakened, the viral fragments can jump from one place to another in the genome, making changes.

Through an analysis of blood samples from pregnant and non-pregnant women, the researchers found it was likely that the same reactivation of retrotransposons seen in mice occurs in humans, too.

Further tests showed that when this process was blocked in mice, the animals developed anemia. The condition, where there's a shortage of red blood cells, is something that pregnant women are particularly susceptible to, due to the extra stresses on the body.

"It's the opposite of what we expected," says geneticist and immunologist Sean Morrison, from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. "If there's ever a time to protect the integrity of the genome and avoid mutations, it would be during pregnancy."

"There are hundreds of these retrotransposon sequences in our genome. Why not permanently inactivate them, like some species have done? They must have some adaptive value for us."

Commonly referred to as 'junk DNA', retrotransposons were once dismissed as segments of code that appeared to be of little significance. It's now known thay many of these genetic relics can still kick into action, sometimes even to our benefit.

Here, the team saw the retrotransposons were activating a signaling protein called interferon, which in turn increased hematopoietic stem cell activity.

"This work changes the way we think about mechanisms that regulate tissue regeneration," says Morrison.

"We've only shown it so far in the blood-forming system, but we speculate other kinds of stem cells also co-opt retrotransposons and immune sensors to activate stem cells during tissue regeneration."

Not only does the new study show how much of a misnomer the term junk DNA is, it also adds to our understanding of the natural defenses deployed to keep mother and baby safe during pregnancy.

As far as humans go, DNA passed down from viral infections in our ancestors make up around 8 percent of our whole genome. Scientists are still learning about how important this source of coding could be.

"These insights help us understand some of the underlying mechanisms that contribute to anemia during pregnancy," says geneticist Alpaslan Tasdogan from the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany.

"Our next step is to initiate a clinical trial to deepen our understanding of how retrotransposons function in patients."

The research has been published in Science.