November 14, 2024

A radical stem cell transplant has significantly improved the blurry vision of three people with severe damage to their cornea.

The clinical trial, which took place in Japan, is the first of its kind in the world, and a significant advancement for stem cell research.

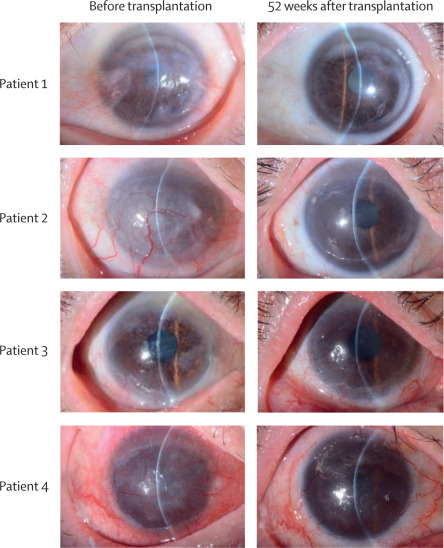

Two years after the operation, no serious safety concerns have come to light, and from the outside looking in, all three corneas look much more transparent than they once did.

Four participants were involved in the study, all of whom suffer from a disorder that causes scar tissue buildup on the cornea, called limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD).

If the cornea is imagined as the 'transparent window' at the front of the eye, then the limbus is similar to its frame, holding the glass to the white ball.

This crucial framework also contains a hearty supply of stem cells, which are ready to replenish any worn-out units in the cornea, like little windshield wipers, keeping the glass clear of fogginess as we age.

Without the vigilance of the limbal stem cell community, gradual vision loss is inevitable.

Today, people with LSCD in one eye can have their scar tissue surgically removed and replaced by a slice of healthy cornea from the other eye. But if the loss of limbal stem cells extends to both eyes, there needs to be a donor transplant.

Of the 12.7 million people who experience cornea-related vision loss worldwide, transplants are available for just 1 in 70. Even for those who do receive a transplant, graft survival is often a problem; there is always a risk of rejection.

That's where the potential of induced pluripotent stem cells ( iPSCs) comes into play.

These all-powerful units are converted from the cells of any human's body. Once reprogrammed back into an embryonic-like state, they propagate indefinitely, with the ability to shapeshift into any type of adult human cell, including those of the cornea.

In 2023, researchers in the US announced they had used limbic stem cells to restore vision in two patients with corneal damage up to a year later.

Now, scientists at Osaka University Hospital in Japan have gone a step further and used iPSCs, derived from healthy human blood cells, to restore vision.

In the lab, the resulting iPSCs were coaxed into corneal epithelial cell sheets (iCEPS). These sheets were then transplanted over the patients' cornea after scar tissue was removed, and a protective contact lens topped it off.

Some seven months after the transplant, all four patients showed improvements to their vision. A year after, however, the vision of patient 4, a 39-year-old woman with the most severe vision loss of the cohort, had once again regressed.

The best improvements to vision were seen among patients 1 and 2, a 44-year-old woman and a 66-year-old man, respectively.

Researchers suspect patients 3 and 4 may have not shown the same improvement because of an insidious immunological response to the transplant. None of the patients were given immunosuppressive drugs, apart from steroids.

Researchers have previously used iPSCs from a patient's own skin to restore vision in those with degeneration of the macula – at the center of the retina – but this is the first time scientists have achieved a similar feat for this other form of vision loss, and without using materials derived from the patients' own cells.

While these small trials are extremely hopeful, such procedures remain highly experimental and potentially dangerous. Far more research needs to be done to assess their safety and efficacy.

"To our knowledge, this study provides the first description of iPSC-derived cell constructs being transplanted into or onto patients' corneas, and it represents a promising future treatment option for individuals with an LSCD," the team from Osaka University Hospital concludes.

They are now planning a multicenter clinical trial to "build on the encouraging results."

The study was published in The Lancet.