November 22, 2024

A new company based at the University of Waterloo’s startup incubator has developed a way to test for concussions using saliva.

The tests are the brainchild of HeadFirst, whose team includes CEO and co-founder Andrew Cordssen-David — a former Quebec junior hockey player.

Born in Montreal, Cordssen-David grew up south of the border playing hockey before he headed to the QMJHL for a few years.

Standing six feet five inches tall, Cordssen-David said his size forced him to play a more intimidating role when he suited up for various teams in Quebec. His physical play resulted in plenty of concussions, allowing him to get used to the testing system.

“That was a part of my game, racking up penalty minutes, hits and fights and things like that,” Cordssen-David told Global News.

“So I got exposed to a lot of the sideline concussion tests that existed from a young age.”

After his junior hockey career, he landed at the University of Waterloo, where he played for the team as well as studying business and science.

“When I ended up going to university and doing my master’s, the master’s was really focused around identifying a problem and finding a solution to that problem,” Cordssen-David explained.

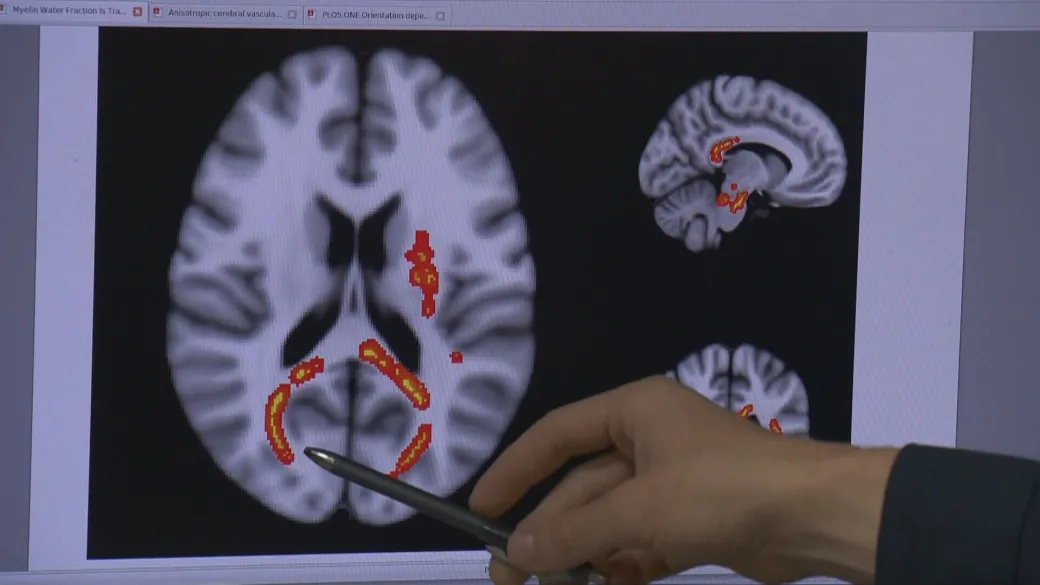

“And for me, the first thing that came to mind was concussions and the subjectivity of the testing that exists today.”

During his playing days, Cordssen-David believed he ended up back on the ice despite possibly having a concussion.

“I didn’t have really a severe concussion at the time, but I knew something was off. I knew something wasn’t right,” he said. “But I passed all these questions at one point and I got put back into play.”

He said some of the questions athletes are asked are about the timing of the game or to name all of the months backwards. Cordssen-David believed there was a better way to test for concussions.

UWaterloo professor Marc Aucoin also shared a similar interest in concussions and approached Cordssen-David with biomarker research, which is behind the new company’s technology.

“I’ve been involved with my sons’ hockey and lacrosse teams and I’ve seen first-hand how challenging concussions have been with kids who play these competitive sports,” the chemical engineering professor stated.

He continued to work with Cordssen-David and Shazia Tavir, a scientist at the school, as they developed the concussion.

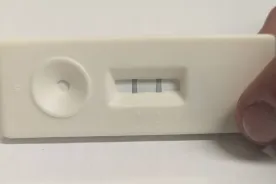

The HeadFirst team came up with a solution that works in a similar fashion to some of the COVID-19 tests, although they begin by using someone’s saliva.

“From there we do a pretreatment process on the saliva to remove all the gook and all the unnecessary stuff from saliva,” he explained. “And then from there, very similar to a COVID test, you drop a few drops onto our assay and our assay will like a COVID test run up.”

Similar to the COVID-19 tests, if two lines show up, you have a concussion, whereas if just one line appears, you don’t.

But don’t expect the product to appear on store shelves any time soon as the HeadFirst team is still in the early stages of development.

It is currently running a pilot test with the athletic department at the University of Waterloo and from there, it will still need to get approval from Health Canada and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

“We’re working on our regulatory roadmap to see approximately how long the timeline will be to get to market, along with estimated costs and sample sizes, things like that,” Cordssen-David explained.

Aside from the more obvious applications such as high-level sports, he believes there are practical uses for the military and in emergency care.

He noted that car crashes and falls at home tend to cause many concussions so having the tests aboard ambulances would be a practical solution.

“Those are really the main focus areas that we think that the device can provide the most value,” he said.