November 23, 2024

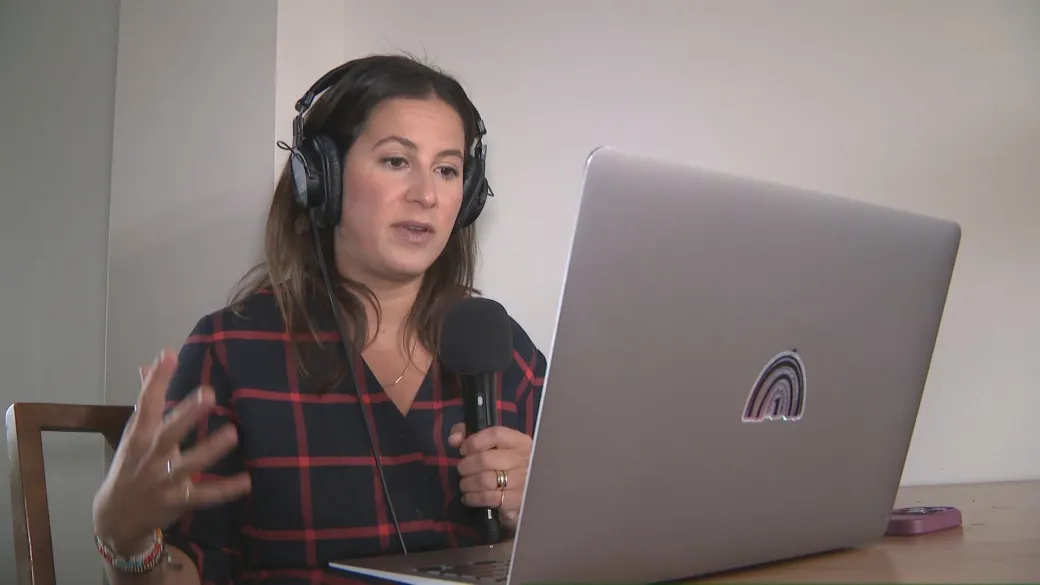

Alyssa Pinelli’s joy quickly turned to fear in 2019 when she found out she was miscarrying a week after finding out she was pregnant.

“We found out baby would be due in June, and then a week later, I experienced some bleeding, and it led to the horrific path it led to,” Pinelli says.

Doctors quickly discovered that the Brockville, Ont., woman had an ectopic pregnancy that had ruptured. An ectopic pregnancy is when the fetus develops outside of the womb, like in a fallopian tube, making it non-viable and life-threatening to the mother.

“I think my whole world just came crashing down again because it was so back and forth with doctors on what was happening with me… I couldn’t wrap my mind around it,” Pinelli recalls.

Though she received excellent physical treatment, Pinelli says mentally, the experience took a toll.

Despite her already having two children, she says she has struggled to return to daily life after the loss, and the fears it could happen again — especially when she sees other people’s pregnancy announcements.

“I still think about that surgery every day, that still lives in my mind,” she said.

“My family doctor did what she could, but I felt there was no discussion with me afterwards to be like this is a community you can reach out to that talks about this.”

Pinelli says she ended up doing her own research to find a local community for pregnancy loss in Brockville to find support.

Dr. Modupe Tunde-Byass is an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Toronto, who also works at North York General Hospital and has studied the impact of miscarriage on women.

In a recent study, she found that many women in Canada have some mental symptoms following a miscarriage, which are often undiagnosed and minimized on average.

The study found that one in three women will have post-traumatic stress disorder, 24 per cent will complain about moderate to severe anxiety, and almost about one in 10 would also have severe depression within one month after they’ve had their loss.

“What’s also interesting is that this can go on for even six to 12 months after the miscarriage, so this is quite profound. There’s quite a profound impact on the mental wellness of women undergoing miscarriage,” Tunde-Byass said.

She says it’s important for doctors to look beyond the medical impacts of miscarriage.

“It’s not just the medical, but the emotional aspect, which is the PTSD, the anxiety and also the depression. So our focus should also look at that miscarriage from that lens, too,” Tunde-Byass notes.

Tunde-Byass says it’s also essential to know the mental impact pregnancy loss has on fathers, which she notes is not insignificant.

Tunde-Byass hopes that talking about miscarriages more removes the stigma, saying it’s “a common condition, which no one talks about.”

Secondly, she says, doctors need to look at how to provide better care.

“Compassionate care means we need to listen, we need to understand, we need to move away from just medicalization, but also treating the emotional and mental impacts of miscarriages,” the doctor says.

She is advocating for health-care providers to be better educated on how to treat those experiencing a miscarriage.

Julia Gartland, 34, is a mother of two from Kingston, Ont., and says when she was miscarrying her second pregnancy on Mother’s Day in 2020, she felt a lack of support.

“I just had this gut feeling something was wrong,” she recalls.

When she started to lose the pregnancy four months in, she went through almost two months of bleeding trying to pass pregnancy before doctors would surgically intervene to remove it.

“They don’t think about the mental toll that it takes on you. They don’t think about the surgery happened, but how long did it take for it to happen? Were there complications? Did it take this person this long in order to get it so it was a lot of anger and I didn’t feel a lot of support,” she says.

Gartland says whereas when you leave the hospital with a baby they give you information on being a new mother, there is nothing they give you when you miscarry. She says more needs to be done to support mothers after it happens.

Recalling the experience, Gartland says she felt people were unsure of how to respond to what she had been through, so they ignored it.

“I had a lot of people not understand why I was sad or crying, and I had quite a few people tell me you should be over it by now. It’s been this long… It kind of made me feel not supported and it made me feel as though I was crazy for feeling sad or for feeling upset,” she says.

Pinelli, now the mother of two young boys, hopes her story helps doctors understand pregnancy loss.

“I felt like I was pushed aside at a lot of my appointments. I had one doctor actually say to me, ‘It’s just a miscarriage,’ and to me, it’s not just a miscarriage,” she recalls.

“This is a very sensitive issue and topic that women go through, and I think they just need to be more respectful and aware that this is the worst day of a woman’s life to be told she’s losing a pregnancy, so that’s where I feel I was failed.”

She hopes sharing her experience helps break down the stigma associated with miscarriages.

“I think a lot of women feel like they have to suffer through it alone, and they don’t,” Pinelli said.

“I know for me, I felt like I thought this was my burden; my body failed me. I think that’s part of the stigma as well, as a lot of women feel like a failure in a sense when they’re not at all.”