December 06, 2024

A new report on Canada’s health care system is shedding light on how a shortage of family doctors and other primary health-care providers is affecting access to timely health care in Canada and contributing to crowding in the country’s hospital emergency rooms.

The report by the Canadian Institute for Health Information says developing a better understanding of why patients are showing up in the ER provides a window into the shortcomings of Canada’s health care system.

The CIHI defines primary care as including family doctors, nurses, dietitians, physiotherapists, social workers and other front-line health care workers who provide routine care for chronic and minor medical conditions, and can refer patients to specialists.

View image in full screen

View image in full screen

The report, by the Canadian Institute for Health Information, suggests one in seven patients who visit the ER had conditions that could’ve been effectively dealt with through primary care.

Of those conditions that could’ve been dealt with in primary care, the report says more than half of them, nine per cent of all ER visits, could’ve been dealt with virtually through a phone call or video call with a doctor, nurse or other primary care provider.

Those Canadians most likely to use the ED for primary care were young children, people who live in rural or remote areas, and people who reported not having access to primary care.

View image in full screen

View image in full screen

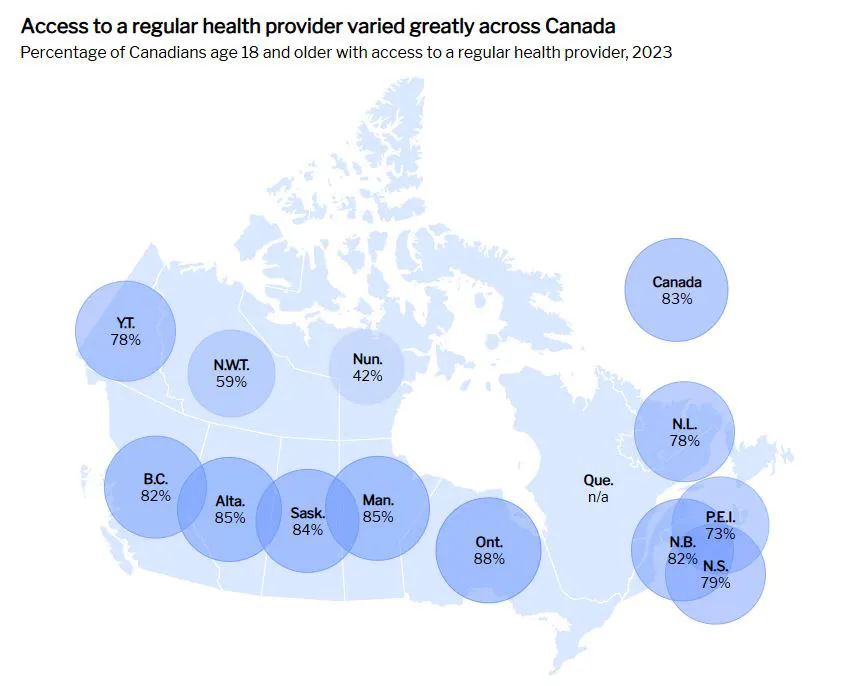

The CIHI report says 17 per cent of Canadians report not having access to a regular health care provider such as a family doctor or nurse practitioner, the lowest among 10 high-income countries in a 2023 study.

The percentage of people who do have access varies widely across the country, from 88 per cent in Ontario to 73 per cent in Prince Edward Island.

The situation is even more acute in sparsely populated areas of rural and northern Canada, with only 42 per cent of people living in Nunavut saying they have access to a regular health care provider.

View image in full screen

View image in full screen

The report says adults in the age group 18 to 34 were the least likely to report that they had access to a regular health care provider (74 per cent) while older adults age 65+ were the most likely to report access (92 per cent).

The most affluent 20 per cent of Canadians were also slightly more likely to have a regular health care provider (84 per cent access) compared with the 20 per cent of those with the lowest incomes (80 per cent access).

On the shortage of primary health care providers, the report says “more family medicine residency positions are going unfilled and, compared with 5 years ago, growth in family physician numbers has slowed. Family physicians also see fewer patients than they did 5 years ago, while the number of nurse practitioners is growing, that may not be enough to satisfy Canadians’ need for primary care.”

As for solutions, the report says while “emergency departments are at capacity and are understaffed,” and “increased access to primary care may be one factor that could reduce ED visits, it is not enough, on its own, to solve emergency department overcrowding.

For this, the report concludes “we need an approach that addresses hospital capacity and capacity in other sectors of care, such as home care and long-term care, performance management and accountability and broader population needs.”