December 06, 2024

A decline in motor skills is a hallmark of Parkinson's disease, regularly taking the form of slowness, rigidity, and tremors. Yet the condition commonly affects other neurological functions as well, impacting mood and causing a decline in cognition.

A drug that blocks a key receptor linked with blood pressure has shown promise recovering memory in models of vascular dementia, inspiring researchers from the University of Arizona to test the treatment on mice with Parkinson's-like symptoms.

Called PNA5, the short peptide is an attractive choice of medication given its affinity for its target and ability to be broken down safely in the body. The researchers analyzed the memories and tissue samples of the mice to determine whether changes could be attributed to the drug.

The team concluded doses of PNA5 reversed some signs of cognitive decline in the mice, while a reduction in the activity of immune cells called microglia, which are thought to contribute to cognitive decline when they get pushed into overdrive, was observed in their hippocampus.

"With PNA5, we're targeting cognitive symptoms but, in particular, we're trying to prevent further degeneration from occurring," says neurobiologist Kelsey Bernard. "By going down the protective route, we can hopefully prevent cognitive decline from continuing."

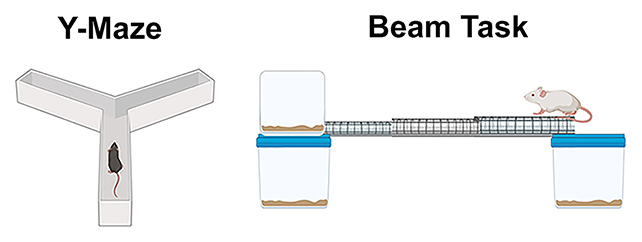

The treatment in the mice was enough to improve recognition memory and spatial working memory, the researchers found. The loss of brain cells in their hippocampus was also slowed when PNA5 was introduced.

By calming the microglia cells down to a more normal state, it's thought that PNA5 can reduce inflammation in the brain, and stop some of the havoc that's caused by the body's out-of-control defense system.

"Normally, microglia are looking for things like viruses or injury and secreting substances that block off the damage," says Bernard.

"In Parkinson's disease, when they're constantly activated, microglia can propagate further damage to the surrounding tissue. That's what we see in Parkinson's brains, particularly in regions associated with cognitive decline."

PNA5 is produced in the lab by building on the vasoconstricting hormone angiotensin, and researchers have already made progress in getting it to penetrate into the brain and last for longer.

While these are promising results, the drug's safety and efficacy needs to be demonstrated in humans. There's still more work to be done in understanding how PNA5 impacts cells in our own brain.

While some the debilitating symptoms of Parkinson's can be well managed with the right care, there's nothing yet that can be done about the dementia aspect of the disease. This study, together with other promising initiatives, gives us more hope for the future.

"When patients are diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, 25-30 percent already have mild cognitive impairment," says neurodevelopmental biologist Lalitha Madhavan. "As the disorder progresses into its later stages, 50-70 percent of patients complain of cognitive problems."

"The sad part is we don't have a clear way to treat cognitive decline or dementia in Parkinson's disease."

The research has been published in Experimental Neurology.