December 14, 2024

A league of scientists are calling for a critical discussion on the dangers of life forms made up of 'mirror-image molecules', because of the significant risks these creations may pose to global health.

These uncanny organisms are not yet a reality, but the authors think we need to take a long hard look in the mirror before stepping through it.

"Driven by curiosity and plausible applications, some researchers had begun work toward creating life forms composed entirely of mirror-image biological molecules," the 38 experts write in a Science commentary.

"Such mirror organisms would constitute a radical departure from known life, and their creation warrants careful consideration."

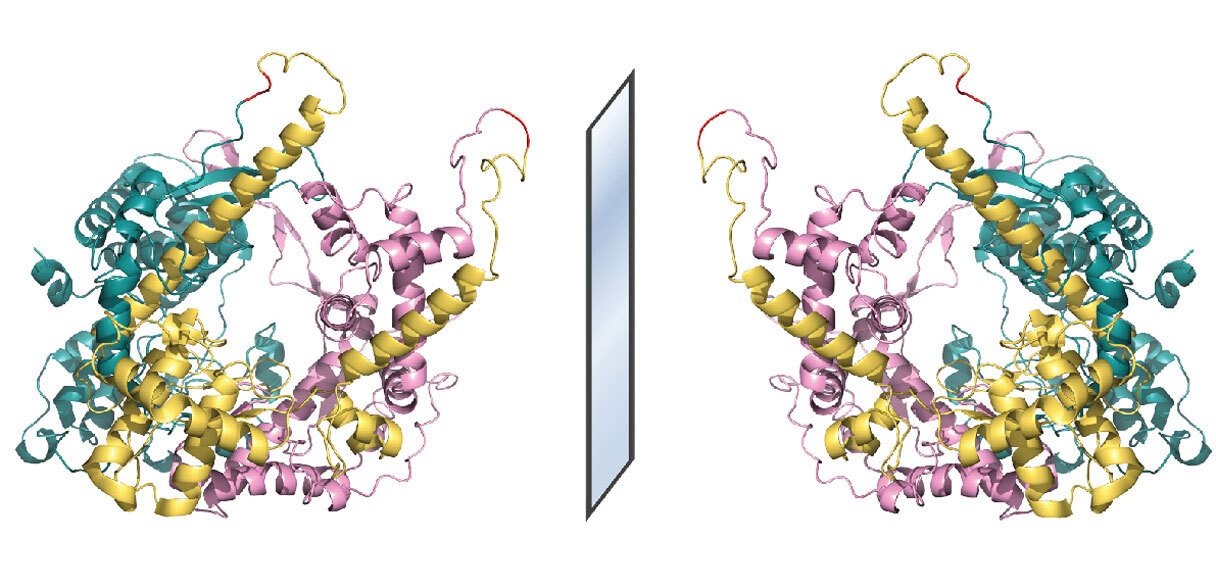

All life as we know it arises from 'right-handed' nucleotides in our DNA and RNA, and 'left-handed' amino acids that come together to form proteins.

This phenomenon is called homochirality. We don't know for sure why it exists, but this defining feature of our biosphere's chemical reactions leaves no room for alternatives.

To add to the confusion, mirror-image alternatives to our amino acids and nucleotides do exist. Which has led some researchers to ponder whether a new kind of life based on these flipped molecules could be created.

Such a feat would start small, with something like a bacteria.

There are a few reasons researchers are interested in creating these bizarro bacteria. Producing molecules from scratch is a laborious process that pharmaceutical companies would rather outsource to bacteria, but to produce mirror-image molecules, they need mirror-image microbes.

In 2016, Harvard geneticist George Church was part of a team that created a mirror version of DNA polymerase, the molecule that coordinates the copying and transcription of DNA into RNA.

Back then, Church was enthusiastic about the advance, describing it as a "terrific milestone" that would one day bring him closer to creating an entire mirror-image cell.

Now he is among the 38 scientists who are warning against it.

The fact that the body can't break down these mirror-version proteins was initially considered a selling point, but that incompatibility with 'natural' life is also what now has scientists concerned.

"There is a plausible threat that mirror life could replicate unchecked, because it would be unlikely to be controlled by any of the natural mechanisms that prevent bacteria from overgrowing," explains biochemist Michael Kay from the University of Utah.

"These are things like predators of the bacteria that help to keep it under control, antibiotics and the immune system, which are not expected to work on a mirror organism, and digestive enzymes."

This back-to-front life form may be limited by its own organic incompatibility. Our molecular chirality makes us compatible with the molecular makeup of the organisms we break down for food, and it's quite likely that mirror bacteria would struggle to survive without food that reflects its own makeup.

But the dozens of scientists behind the new paper agree that we cannot afford to play with such unknowns, even though the threat is far from imminent.

"It would require enormous effort to build such an organism," says Vaughn Cooper, a microbiologist from the University of Pittsburg. "But we must stop that progress and have an organized, inclusive dialogue about how to effectively govern this.

"There is some exciting science that will be born because of these technologies that we want to facilitate. We don't want to limit that promise of synthetic biology, but building a mirror bacterium is not worth the risk."

The paper is published in Science, with an accompanying technical report published by Stanford University.