January 01, 2025

Brain damage can cause major personality changes, and in some rare cases, patients can become pathological jokesters, unable to suppress the urge to make silly jests or childish puns, even in inappropriate situations.

A notable case study from 2016 describes a 69-year-old man, who suffered a stroke and developed a compulsive need for humor.

The patient's desire to share a knee-slapper was so great, he would often wake his wife during the night just to tell her one of his funnies. So she kindly asked that he write them down instead.

When first meeting a team of neurologists, the man brought along "approximately 50 pages filled with his jokes, most of which were either puns or silly jokes with a sexual or scatological content."

The man was diagnosed with Witzelsucht, which is a collection of symptoms characterized by an incessant desire for humor. Oftentimes, the jokes are inappropriately timed or of an offensive nature, yet the joke-teller remains oblivious and highly entertained by their own wit.

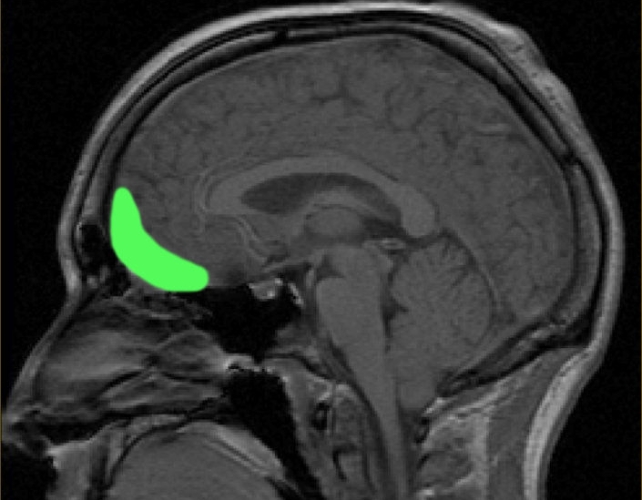

The term Witzelsucht (a combination of the German words for 'joke' and 'addiction') was first introduced in 1890 by a German neurologist named Hermann Oppenheim, who noticed that damage to the right frontal lobe, either through injury or disease, sometimes led to overly humorous behavior in his patients.

In 1929, the German neurosurgeon Otfrid Foerster was conducting brain surgery on an awake patient, when he prodded a certain part of the brain that caused the patient to suddenly start cracking puns in Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and German.

This helped neuroscientists narrow in on the area involved in humor, but in all the decades since this discovery, it's still not entirely clear how often witzelsucht occurs, or how it can be treated. Case studies are few and far between.

Neurologist Mario Mendez has authored more than most. He and his colleagues at UCLA were the ones who received 50 pages of jokes, and they have reported several other case studies of Witzelsucht since 2005.

Today, scientists know that Witzelsucht can often exist alongside or overlap with another collection of neurological symptoms called moria, which is characterized by pathological giddiness.

Both behavioral changes are associated with damage to the orbitofrontal circuit, which is involved in decision-making and which can be associated with tactlessness when damaged.

Just a few years ago, Mendez and UCLA colleague Leila Parand shared the story of a 63-year-old man, who had been shot in the head, losing much of his right frontal lobe and part of his left orbitofrontal cortex.

The individual, who once suffered from frequent depression and suicidal ideation, suddenly showed persistent feelings of mirth and happiness in recovery, at one point declaring, "You will never find me in a miserable state".

"On examination, he was observed to be unconcerned, frequently jesting, punning, or making light-hearted teasing comments to others, and generally not taking his situation seriously," his doctors report.

"He would occasionally [exhale against a closed mouth] to self-inflate his craniotomy defect in order to surprise and amuse anyone around him."

While there is no standard treatment for Witzelsucht or moria, Mendez and his colleagues at UCLA note that clinicians may start by prescribing serotonin reuptake inhibitors. These often don't work, in which case other treatments are tried, such as psychoactive antiseizure medications or atypical antipsychotics.

But while some drug mixes seem to alleviate episodes of laughter in certain individuals, it's harder to get rid of the compulsion for jokes.

In a paper from 2019, psychiatrists wrote that research on moria and Witzelsucht has helped us better understand patients with neuropsychiatric disease.

These symptoms, they say, "shed light on the neural underpinnings of some of the most complex positive mental phenomena that make up human life, including humor, creativity, and joy."

It's hard to make light of that.