January 12, 2025

The University of Windsor is working with Canadians who are sharing their stories of medical gaslighting.

“This kind of thing can lead to death,” said Marissa Rakus, study coordinator.

“It was extremely traumatic,” said Katrina Dobson, a victim of medical gaslighting.

While a newly-coined term, medical gaslighting has been around for decades, affecting mostly women and minority groups.

Medical gaslighting can be described as the experience of being disbelieved, not taken seriously, and dismissed by medical providers – with many health issues being reduced to weight, hormones or mental health problems.

Katrina has been diagnosed with a variety of chronic illnesses like Eagles syndrome, a rare bone disease that causes sharp pain in the neck; hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a genetic connective tissue disorder; and mast cell activation syndrome, a condition that causes reoccurring allergic reactions.

She has experienced medical gaslighting in more than one situation – almost costing her life. “I sat in the hospital for five hours. My throat was closing. I couldn’t breathe. I was red,” said Katrina.

“And then finally, once I got into the room, the nurse asked me if I purposefully ingested the walnuts and that I don’t have a real reaction.”

In one instance the hospital even called her husband to confirm her need for a breast pump.

“I was just completely flabbergasted,” said Landon Dobson, Katrina’s husband.

“Having them phone me and asked me like if she was actually, in fact, breastfeeding. Yes, she was. And they didn’t believe her.”

Situations like this have caused Katrina to doubt herself and avoid further doctors visits.

“I would have always felt like a hypochondriac, like I was as a child in pain. It’s in your head. You’re lazy,” said Katrina.

“It’s to the point now where I leave (my medical issues) and that’s not healthy for anyone.”

But Katrina is not the only person who has had to go through situations like this.

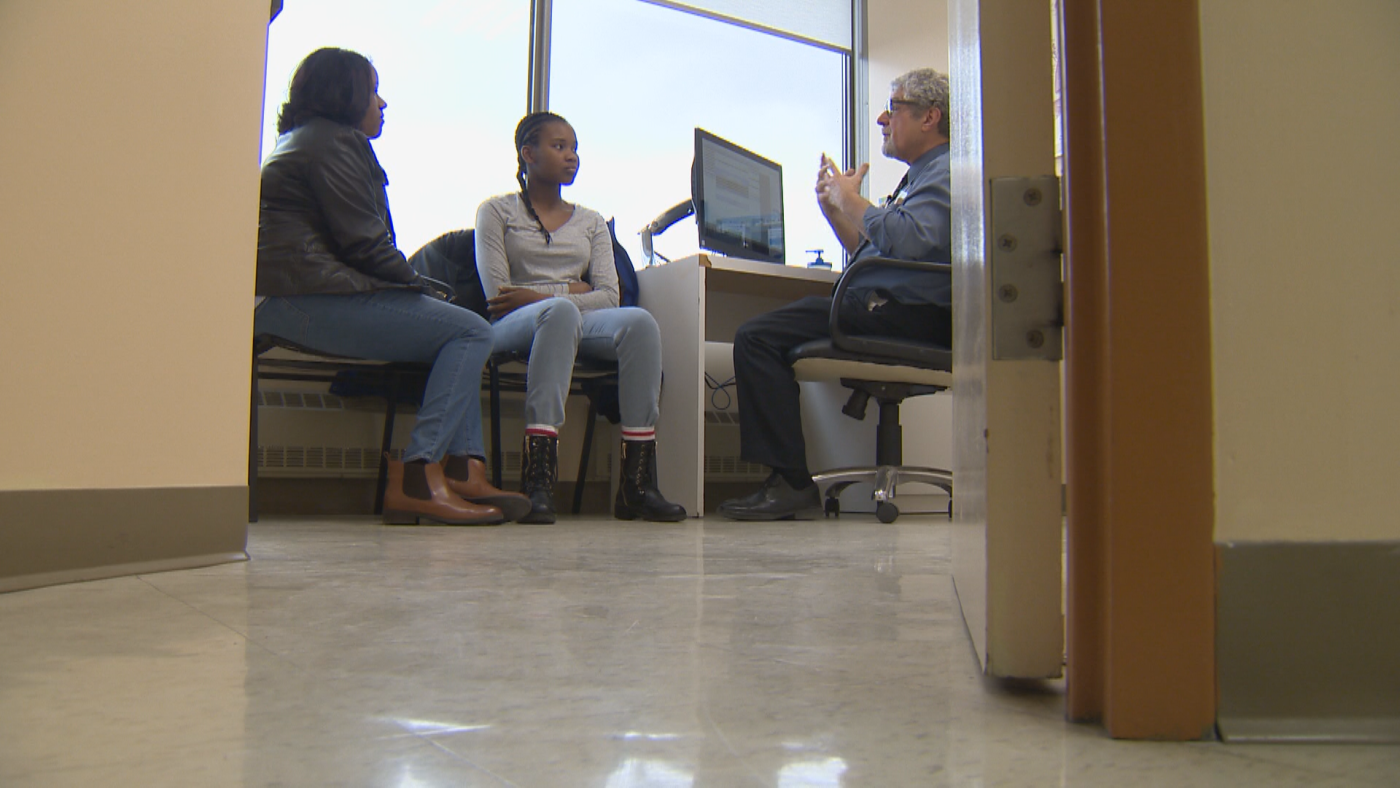

The University of Windsor is conducting a study of medical gaslighting experiences across Canada.

Researcher Marissa Rakus says almost every woman you meet has at least one story of medical gaslighting.

“The medical system was built by men for men,” said Rakus.

“Women weren’t even included in medical clinical trials until (the) 1990s, which is really not that long ago.”

Rakus said that a lot of these issues boil down to lack of research and teaching, adding that this is a systemic issue, not an issue with individual doctors.

“It comes down to the actual training done in the medical schools,” said Rakus.

For women and people of minority groups, Rakus says health concerns require more research and training to be treated effectively — adding medical gaslighting can cause patients to stop believing in their lived experience.

“You feel like you’re going crazy, you’re getting anxious, depressed, isolated from those around you because you’re in so much pain or whatever the situation may be leading to trauma, too,” said Rakus.

She added that doctors need to be more open and willing to listen.

“It’s not all about actually giving a diagnosis or, you know, having an answer for them. It’s I hear you. I’m listening to you, and I will be on this journey with you to help try and figure it out,” said Rakus.

The Dobsons say advocating, researching, joining support groups and bringing support with you to medical appointments can help reduce the risk of experiencing medical gaslighting.

“Everybody does need to speak up or else there’s not going to be change,” said Katrina.

“Keep going and make sure you get a second opinion and just advocate for yourself,” said Landon.

Rakus adds teamwork is key.

“I 100 per cent think it needs to be a collaborative effort because, you know, the patients’ lived experience and what they are going through is leading what the doctor is investigating,” said Rakus.

The University of Windsor’s study is accepting participants digitally until February.

View image in full screen

View image in full screen